|

This is the sixth and final blog by Paul Courtright as his personal revisit comes to an end. Every foreigner who spends a few years in Korea ends up with their favorite Buddhist temple. It may be the small temple near where they live or it may be a larger, more well-known temple they visited frequently. Well, I cheated. I have two favorite temples: 송광사(Songgwangsa) and선암사(Sunamsa). They are separated by a 7 km hike in 조계산(Jogyesan Provincial Park) near to 순천where I worked for a while. Why my favorite? The sounds, the smells, the peace and quiet, and, of course the beauty of the temple grounds themselves. I skipped class on Friday, hopped on an intra-city bus and made my way to 송광사for the first time in almost 38 years. This blog could simply be a bunch of pictures (mostly of roof lines, my favorite) but that would not capture the smells—pine trees, incense, old wood, and charcoal and the sounds—the gurgling stream, the 목탁(wooden instrument), and the melodic chanting. 송광사had it all.  Getting there was a bit of a slog. I relied on Googlemaps for instructions and, by and large, it worked but one item missing from the instructions was an hour-long walk--and I’m a fast walker--to get from the last bus stop to the temple. The guy who sold me the ticket said: “It’s near.” I enjoyed the walk but I would not call a one hour walk “near”. Add another 30 minutes and I could have walked between the two temples! Was I disappointed with 송광사on Friday? Well, a bit. I can’t blame the monks. It’s a working temple and there are many areas used for study and living. In the intervening years since I was there last there’s been a huge influx of tourists and the monks have had to close off areas of the temple grounds if they are to have their own peace and quiet. I could not explore to my heart’s content as I could so long ago. Would I go back? You bet. But, I’d change my schedule. I would arrive at one of the two temples in the late afternoon and spend the night nearby. That would allow time to be in the temple grounds in early evening and then early morning, when light is the best. I’d hike in the morning to the other temple. If I had all of the time in the world, I’d spend the night there. The sights, sounds and smells have always captured me—and they still don’t want to let go. Maybe next year?

2 Comments

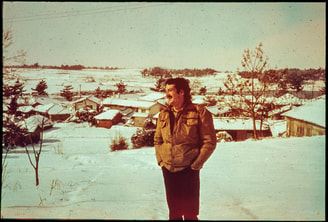

this is the fifth installment of Paul Courtright's blog.... Tomorrow, Thursday, is the last day of my two week language training. My last day should be Friday but I decided to play hooky on Friday so I can visit 송광사before I leave for Seoul. I’m experiencing only minimal guilt—my adolescent pleasure in playing hooky prevailed. Re-learning Korean after 37+ years has been tough and I certainly will not say that I have “re-learned” the language. Daily one-on-one three-hour lessons have been exhausting. It probably would’ve been easier to have one or two others in the room with me to give me a break from time to time—let others make a few mistakes rather than me all of the time! I had hoped that my home-stay, with a family including 3 boys, age 6, 7, and 11, should have given me more opportunity to practice but they were keen to practice English. They speak to me in English and I respond in Korean. Not the best but they’re a nice family so it was a good time. The highlight of each day has been the afternoon. Lessons end at 1230 and the brother of a Korean friend, on leave from work, was happy to be with me in the afternoon. We did a lot of hiking, visiting temples, and some of the 5.18 sites in Gwangju. We spoke only in Korean—that is, until I fumbled, which was rather often. When we all learned Korean long ago, the focus was on learning how to speak and understand others. My Gwangju class used a workbook—yep, I felt like a little kid again. While there was some good information in it, it involved a lot of reading. I would read a sentence, stumbling over the words of course, then realize that I recognized the words and meaning—just not in written form. My teacher and I both felt that the workbook was boring so we often jettisoned it, starting a conversation using the particular pattern or words I was re-learning. In the intervening years, the Korean language has changed. There are many more English words being used; unfortunately they are written in 한굴. More than once I’d stumble through trying to pronounce it to be informed that it was an English word, not a Korean word! Yep, felt pretty stupid. The other change, which I find a bit sad, is that some words that really are part of the culture have been dropped from use: 가개, 목욕당, and 다방(shop, bath house, tea house) are three of many. Years ago, I had to learn words for ulcer, leprosy, eyebrows, and the like. I no longer need these words but they still clutter my brain. I’m trying to replace them with words that have more meaning in my life now: retired, witness (related to 5.18), and memory (or lack thereof!). My onion-skin page Peace Corps dictionary is still the best thing around and I don’t go anywhere without--now I also have to carry a magnifying glass. While Koreans look up words on their smart phones I’m flipping through my 50 year old dictionary. I also keep a small notebook where I write words, phrases, and patterns to study while riding the subway. Needless to say, I’m the only one whose eyes are not glued to a device. Every evening and morning I sit at a 커피솦(coffee shop), sadly, not a 다방(tea house), with coffee, notebook, dictionary, magnifying glass and, when I can stand it--the workbook. Learning Korean at 25 was a challenge. Trying to re-learn it at 64 has been rather humbling.  This is the fourth in a series of blogs by Paul Courtright who is on a personal revisit back to Korea. Many of us have been lucky enough to have come back to Korea to places we lived and worked forty or more years ago. Most of these towns grew, swallowed up by development of one form or another. Looking at pictures we took back then helped to etch our old life permanently in our brains. Trouble is, sometimes the physical changes where we lived were so massive that those old images cannot be recreated. So, we look at our pictures. When that happens, our emotions get mixed up—sad about the changes but also happy to see the improvements. 호헤원was a bustling village when I lived there from 1979-80. The village was in 나주군on the outskirts of 광주. Egg production in the village was on a massive scale. The entire village was part of a cooperative that produced thousands of eggs every single day. Trucks rolled into the village daily to pick them up and then sell them in surrounding towns. 호헤원was a prosperous place. A by-product of that prosperity was the over-powering smell of chicken shit. And, yes, I ate lots of eggs. Tuesday I was back in 호헤원. The village has been virtually abandoned. Part of it was swallowed up by a factory and another part was paved over for a road reaching the factory and other large businesses that have invaded the area. The centre of the village, near where I lived, was still intact—the village office, a monument to 육영수(Park Chung-hee’s wife--she visited in the early-1970s), and a small community centre still stand.The rest is a jumble of empty houses and chicken coops, collapsed roofs, and weed-filled lots. The house of the woman who washed my clothes no longer stands but the small tree she had next to her chicken coop has become mature, softening the scene. The monument to 육영수remains well-tended with the azalea late in bloom—someone still comes around to keep it clean and tidy. Sometime between when I lived there and its abandonment, the small paths through the village were transformed from muddy ruts to pavement. So, what happened to this prosperous little place? It was better off than surrounding communities and I would have guessed, back then, that it would continue to grow. In fact, it was probably doomed from the beginning: it was a leprosy resettlement village. Forty years ago the residents of the village were either under six years of age or over forty years of age. All young people were packed off to school far from the village to avoid the stigma of being from a leprosy village. Villagers were committed to ensuring that their children’s lives were not touched by leprosy in any way. It is not surprising that children did not return to the village after schooling. There were no young people to keep the egg business going and the village died. An “old folks home” occupied the top floor of the village office for a while—even that is now gone. The visit was bittersweet. The young people that I never knew got on with their lives. I hope the elderly live comfortably. One thing hadn’t changed: even with the absence of chickens the smell of chicken shit lingered….everywhere.  This is the third in a series of blogs by Paul Courtright who is on a personal revisit in Korea. We always hear: the victors write the history. Certainly, for many years after the Gwangju Uprising the official history was written by the Chun Du-Hwan government. It should come as no surprise that the government narrative did not reflect the fact that they perpetrated the massacre. And since then? It is unfortunate that in the intervening years there was no investigation to fully capture the uprising. Now there is a push to get a complete historical record. Although Gwangju was the epicenter, Naju, Mokpo, Damyang and other Jeonnam towns were also involved. To capture the full story, interviews will be needed with thousands of people—only then can the full breath of the event be understood. Each of us who were witnesses actually only witnessed bits and pieces of the much larger picture. On Tuesday I got a taxi in the small town of Nampyeong, about 15 km south of Gwangju, to go to the leprosy resettlement village I lived and worked in from 1979-80. Along the way, my taxi driver, who was about my age and from Nampyeong, and I got into conversation about 1980. He was surprised that I knew the leprosy village since the village no longer exists. He told me that his brother was killed during the uprising. Soldiers fired upon his vehicle on the road between Nampyeong and Gwangju. My photographs of bullet-ridden vehicles had appeared in the Gwangju newspaper just that morning, along with my interview. Was his brother in one of those vehicles? Has his story been told? Last week in Seoul I met a Canadian historian and mentioned to him that, as the first PCV to get out of Gwangju (the day before the military re-took the town) I’d gone immediately to Seoul to give my account to the U.S. Embassy. Unfortunately, that official debriefing never took place and was limited to my contact with the Peace Corps office. My historian friend said that that’s not what the cables from the US Embassy to Washington DC said. That shook me—something wasn’t right. He and others understood that I’d debriefed the US Embassy about what I’d seen in Gwangju. He sent me a copy of the cable and it reads: “Four Peace Corps Volunteers could not be reached. (We have talked with PCV Paul Courtwright)” (sic) In fact, given the date of the cable and the wording, I realized that it was just an acknowledgement that I had contacted the Peace Corps office after I got to my village--after taking a back way, over the hills, to get out of Gwangju. This was not a debriefing. The take home message: the terseness of cables leave them open for multiple interpretations. The Jeonnam provincial capital building has been retained as a museum and it was really helpful to go and see it after over 38 years, particularly because it’s one of the settings in the memoir I’m writing. During the uprising I wrote down everything that happened—not for the sake of posterity but because it was the only way I could get some sleep at night. Even with my notes however, some things were forgotten. I thought the building was just two stories—it is actually three stories. I had to go over the hills separating Gwangju from where my village was located and I had lost track, in my mind, of some of the terrain. Being back in my village and traveling the short distance—only 15 km--between Gwangju and Nampyeong helped me remember the “feel” of the land. Needless to say, the trees have grown since then and some of the area is now filled with apartment blocks. There are still some aspects of the story of the uprising that remain unclear. I’ve heard that the Korean military had plans to bomb Gwangju—is that true? While the early cables from the US Embassy to Washington DC present an ill-informed perspective of what was going on in Gwangju the later cables are much better informed, balanced and objective. What happened in between these two times? This is the second in a series of blogs by Paul Courtright who is on a personal revisit in Korea.

The Seoul sky was tinged with Mongolian dust on May 4th when my plane touched down. It was good to be back. Settling into my hotel in Seoul I figured that I would have a few days here to see friends, talk to students at Yonsei and Heart to Heart Foundation, and start the process of diving back into Korean language—the first goal of my three weeks here in Korea. The second goal of my time in Korea was to be back in Gwangju to make sure I had accurately captured the sounds, smell and feel of the place in my book. I’m about two-thirds the way through my second revision of a memoir of 13 days around the Gwangju Incident and my plan is to have it ready for publication at the end of the year. Was I in for a shock! Within the first couple days I learned two things: [1] the story of the Gwangju Incident has not been captured. There is no accepted narrative of all that happened. [2] The Gwangju Incident has become a politically contentious issue. Unbeknownst to me, the news media has been clamoring for stories about the event. Although it was not part of my plan, when I arrived colleagues asked if I would talk to the media. Three interviews (two newspaper and one TV) have been completed and it looks like there might be more down the line. I have found it hard to say “no.” How to tell the story? There is no single story. The Gwangju Incident happened over a number of days, involved thousands of people, and covered an area much bigger than Gwangju. No single person could witness it all. The only way that the Gwangju Incident can be told is by capturing the stories of hundreds, if not thousands, of people in Gwangju as well as the surrounding towns. Damyang to the north and Naju to the south both have to contribute. I can only tell my story—it is just one small piece of a much bigger story. More than once I heard that the stories of foreigners in Gwangju are critical—because foreigners are “considered objective”. I don’t know how true that is. I have to admit that I was profoundly shocked that the military would kill civilians. President Moon has requested the establishment of a bipartisan (or non-partisan) commission to do a deep dive and compile the full story of the Gwangju Incident. If this can be successfully undertaken then there is some chance that that, by the time of the 40th anniversary in May of 2020, the next steps to healing the old wounds can begin. I am hopeful. Paul Courtright served in Peace Corps Korea from 1979 through 1981. Over the years, he has been to Korea numerous times including a revisit trip in 2011. He is currently in Korea for a month - his own personal revisit. Paul will be doing a series of blog posts that will be shared here.

Is there anything more humbling than the first day of a two week Korean language class? I think not. Dredging up words, phrases and patterns last used more than 35 years ago had me scratching my head. I experienced brain freeze a few times. I stumbled over words that once flowed smoothly. The folded recesses of my brain hid some simple words, releasing them only when I had thoroughly embarrassed myself. I even had to fill in the blanks in a workbook—was I back at school? Short answer: yes. Did I make mistakes? You bet. Did I feel like an idiot? Most certainly. Three hours of Korean language classwork had me exhausted and wondering if I learned much of anything. I had decided, in advance, to undertake one-on-one language lessons but now I wonder if that was the right decision. It’s nice to share the attention of the teacher—that is, let others make the mistakes which I can then learn from. Tomorrow I will start all over again. I had decided that the best way for me to retain my sanity was to have my afternoons dedicated to exploring Gwangju and the surrounding areas—to be outside. I’m fortunate to have a Korean colleague, from my time working in Tanzania, living here in Gwangju. Her brother is on leave and will be going with me on my afternoon jaunts--and working on my conversation. For our first day we went to the old Gwangju Jeonnam Provincial Office, which has been turned into a cultural centre and park tied to the Gwangju Uprising of 1980. It was the second humbling experience of the day—being in the centre of the uprising of 39 years ago. More on this in future blogs. My afternoon compatriot is a Korean language teacher in a high school. He looked over my workbook (yeah, I felt like a little kid) he commented that it was quite difficult. I had to agree. Of course, deep down I know that my ability to pick up the language is not what it used to be and the workbook will likely always be difficult. Koreans are hooked on a coffee culture and my attempt to get a “coffee” was met with incomprehension. If you want a cup of (plain) coffee you have to ask for an Americano. There are other new words, many also just taking on the English word. I tried to sound out a word I did not know (in ta beu), totally blanked, looked it up in my dictionary and saw: “interview”. What an idiot. I suspect that this week and next I will have many more opportunities to flub, fumble, and forget. Should be fun. |

Details

Friends of Korea

This is a BLOG for and about Friends of Korea. Archives

May 2019

Categories |

2021 L Street, NW

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed